This question has been dancing through my mind for quite some time. On the surface it seems that there should be an easy answer. There must have been a single moment in history where the earth had the highest linguistic diversity. But how do you measure this? What were the driving factors behind the growth and decline of languages on our planet?

While research exists on how a language comes to be and the circumstances from which languages disappear, there doesn’t appear to be an answer to the broader question posed above. I would imagine that this is in great part due to the simple lack of data in this area. No database exists cataloguing when languages were first created and when they stopped being used. Current efforts are working to start this data collection, and while it may be close to accurate for modern times, it is impossible to gather data on all previous languages. There have almost certainly been languages that are simply undocumentable. Perhaps they were spoken by a small tribe in the Amazon that was suddenly and dramatically wiped out by a disease without ever interacting with the rest of the world. How could we possibly know that this language existed? With no research and no data, we are left to consider this question in the tradition of all great philosophers — rambling with great deal of conjecture and hypotheticals.

Before diving into what we now know is a highly theoretical question it is important to establish a shared definition of what constitutes a language. Linguists, scientists, and philosophers have argued about the minutiae of this definition for centuries, but for simplicity’s sake I will use the linguist Robert Lawrence Trask’s definition from his 2009 textbook Language and Linguistics: The Key Concepts. Trask views language as a formal system of signs governed by grammatical rules of combination to communicate meaning. This definition allows us to consider language in a less theoretical and cultural context, and focus more specifically on the number of formal systems that existed at any given time in history.

So let’s dive in. At what point in time were the most languages spoken? One of the fascinating aspects of this question is that there has clearly been a rise and subsequent decline of languages.

Let us assume that when humans first began to create formal systems of signs to communicate meaning there were not very many humans on the planet. Here we do have evidence. Archeologists have shown us that the human population has grown at a remarkable rate, and began from smaller more concentrated groups. This is our baseline: small number of humans, small number of languages. As population grew, humans spread and dispersed geographically. At this time, travel was on foot and without maps so covering distance was difficult. The resulting isolation of spread out groups likely caused languages to adapt and change, creating new languages. This happens slowly, but, to consider a more modern example, is how Latin evolved into and influenced French, Spanish and Italian. We can imagine ancient humans slowly spreading across the globe, languages evolving and expanding with them. Then at some specific moment the decline began.

To explore this transition we move to the opposite end of history: the present. Here we also have concrete data. The UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger estimates that a third of the world’s languages have fewer than 1,000 speakers left, and every two weeks a language dies with its last speaker. The number of languages spoken in the world is declining. So what is causing this? One potential answer lies in colonialism. The British, Spanish, Portuguese, and many others imposed their language as the conquered other parts of the world, culling populations, cultures, and languages in their wake. More recently the US enacted policies in the 1900s to force Native Americans, Native Alaskans, and Native Hawaiians to speak only English, leading to the collapse of many of these languages.

However there are other factors that also contribute to UNESCO’s alarming report. One of UNESCO’s measures for what makes a language endangered is when it is only spoken by older generations. If the youth of a population are not learning a language then that language is less likely to persist. While this requires a great deal more statistical and theoretical foundation, I believe that driving force in youth disengagement is globalization. Less spoken languages are simply less useful in an increasingly globalized culture and world. The dominant languages are more desirable for earning a better living and being able to move around the world. Similarly, because of technology these languages are more available and present than ever.

These two factors have not just influenced modern times but also could have created similar reactions long ago. Simply put, if a population never encountered another language, especially one spoken by a larger group of people, their language is likely to persist. So what creates this interaction? I believe that all of the examples above can be attributed to technological growth. Colonialism was driven by technological advancements in travel. The expansion and interconnectedness of the world is similarly controlled by breakthroughs in travel and communication. This is partially why many of the areas with greater linguistic diversity are those that are difficult to get to, and possess less advanced technology.

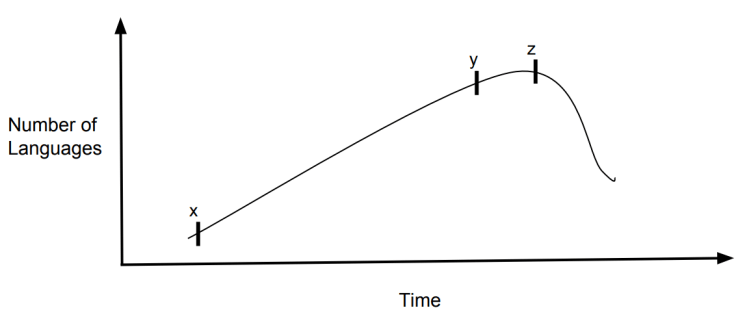

Returning to the key question, we have found two factors that change the number of languages spoken in the world: population increasing language diversity and technology decreasing language diversity. This is a very simplistic view of these interactions, and there are undoubtedly more factors and complicating features, but for the sake of creating a model of language diversity I am going to stick to just these two factors. Visually here is what I am suggesting:

The model shows the curve of the number of languages spoken over time. Moment “x” is when the population spread started to drive up the number of languages spoken. Moment “y” is when technology started to impact this spread by increasing ease of travel. However, this positive impact is quickly turned around at moment “z” as technology drives the number of languages sharply down. Important to note here is that population also hits a tipping point and starts to have a negative impact on the number of languages as sheer volume of people in the world makes it close to impossible for groups to remain isolated.

While this model diagrams a possible path for the number of languages across time, it leaves much to be desired. Moment “z”, the point in time that started this whole quandary is still undefined in both time and number of languages. I remain fascinated by this puzzle. Perhaps with a greater understanding of the influencing factors and the steadily increasing efforts of various international groups to catalogue and keep track of languages we will be able to more closely pinpoint when moment “z” happened and what the world looked like then. Is it possible to reverse the curve? Is it beneficial to reverse the curve? Or perhaps should we as a now global community strive for one universal language. I worry the impact this would have on cultural diversity and knowledge, but that’s a question for a different blog.

Fascinating! More, please.